Bitcoin's Security is Fine

Fears over the declining block reward are overblown

Published Block: 576165

TL;DR — This article comprehensively addresses concerns around Bitcoin’s security model which is funded by the block subsidy and transaction fees. Key points:

The larger the Bitcoin network grows, the more secure it becomes.

Over the long term, an organic security tradeoff will occur between the block subsidy and transaction fees. As network effect becomes larger, demand for block space increases, thus decreasing the need for a block subsidy. We have empirical evidence that this is occurring, and future projections look optimistic.

Bitcoin’s block space is a scarce and unique commodity. It will continue to accrue demand.

The bull market of 2017 wasn’t millions of consumers suddenly using blockchains to transfer money around the world and seeking to minimize transaction, exchange, volatility, and coordination fees.

The price inelasticity of a Bitcoin transactor is high. Even in significantly higher fee environments Bitcoin block space demand will grow.

I’ve paired a song with this article because I think it fits the feel of the piece and adds additional depth.

Block Reward

Approximately every 10 minutes, a new Bitcoin block is created, which contains newly minted Bitcoins (the “block subsidy”) plus transactions (which includes transaction fees paid by the entity sending the transaction). The value of the newly minted coins plus transaction fees is called the “block reward.”

Per Bitcoin’s hard coded monetary policy, the amount of newly minted coins per block decreases over time, eventually reaching 0% in the year 2140 (also known as a disinflationary model). At the time of this article being published, over 83% of all Bitcoins that will ever exist have already been minted, and the current annual inflation rate is just 3.8%. Over 99% will be mined by 2040.

“Indeed there is nobody to act as central bank or federal reserve to adjust the money supply as the population of users grows. That would have required a trusted party to determine the value, because I don’t know a way for software to know the real world value of things. If there was some clever way, or if we wanted to trust someone to actively manage the money supply to peg it to something, the rules could have been programmed for that.” — Satoshi Nakamoto

Satoshi felt that setting a “proper” rate of inflation was impossible (due to the local knowledge problem) and that it introduced a political attack vector, so he decided to remove human decision making from the process. Each time monetary policy is changed or modified, human governance re-enters the system nullifying the certainty of monetary supply. This ultimately leads to less social scalability increasing the risk of network fragmentation and disagreements. A predictable monetary policy is key: Bitcoin’s focus on long-term stability and transparency creates confidence for investors and developers.

In other words, the fixed monetary policy in Bitcoin effectively and directly addresses a property rights problem: Without a hard supply cap it becomes uncertain what share of the total future stock any particular holder owns; as a result, variable supply policies almost always dilute individual ownership shares of money over time. Because supply caps solve this property rights problem, then those currencies tend to have increased value.

I won’t spend more time diving into Bitcoin’s monetary policy, as I consider that a separate topic which requires an article exclusively (which I will be releasing sometime in the next few months).

So why does this matter? The block reward incentivizes miners to protect the network. As inflation trends towards zero, miners will increasingly obtain an income only from transaction fees. Some worry that transaction fees alone won’t provide adequate compensation for the miners. In storing large sums of wealth, security and trust are critical.

https://plot.ly/~BashCo/5.embed?share_key=ljQVkaTiHXjX2W41UiqzCn Created by BashCo

Bitcoin’s Security Model

“In a few decades when the reward gets too small, the transaction fee will become the main compensation for [miners].” — Satoshi Nakamoto

Bitcoin’s existing UTXO set (ledger) and new blocks are protected by game theory and physics. Bitcoin uses proof-of-work (PoW) to make changes to the ledger difficult, which eliminates trust and introduces an external cost for any would-be attacker. The miners buy hardware (capex) and electricity (opex) with the expectation of receiving their portion of the block reward based on work spent (hashes). The block reward financially incentivizes miners to behave properly.

As the price of BTC increases, the value of the block reward increases as well, which incentivizes miners to bring more hashrate online to mine. The higher the hash rate of a cryptocurrency network, the more expensive to 51% attack.

The security budget protects the network against 51% attacks which primarily occur on the tip of the blockchain, rather than an entire chain rewrite, which would require significantly more resources.

In the early stages of the network, Bitcoin miners are rewarded more heavily by the block subsidy than transaction fees. With Bitcoin’s disinflationary monetary policy, approximately every 4 years the block subsidy drops by 50%. This creates both volatility and a price increase: if demand remains constant (or increases), the reduction in supply means demand is chasing less freshly minted Bitcoins hitting the market. This effect brings in new speculators, which is part of the beauty in its design, as the supply shocks bring greater awareness to Bitcoin.

“As the number of users grows, the value per coin increases. It has the potential for a positive feedback loop; as users increase, the value goes up, which could attract more users to take advantage of the increasing value.” — Satoshi Nakamoto

While the two represent the same security budget, the block subsidy and transaction fees are very different. For the block subsidy, its value is both as a rational way to issue new Bitcoins and as a viral FOMO loop built into the protocol, which increases the number and network effect of believers in Bitcoin. It further stretches out the need for transaction fees to solely provide security. Hence why it’s called a “subsidy.”

Over the long term, an organic tradeoff will occur: as network effect becomes larger, demand for block space increases, thus decreasing the need for a block subsidy. While we don’t know why Satoshi chose Bitcoin’s issuance schedule specifically, we can speculate. Four years between halvenings is a long time to plan and build. In similar duration, we give a US President four years to make things happen for an entire nation.

With modeling done by Awe and Wonder we can see that around the year 2030 transaction fees will begin to consistently represent a healthy portion of the block reward. When transaction fees represent greater than 50% of the block reward for long periods of time (YoY), Bitcoin evolves to surviving more on transaction fees.

Chart and projections by Awe and Wonder. Y-axis is % of Bitcoin’s market cap daily.

Critics often argue that transaction fees alone won’t provide adequate security. But what is an appropriate security level? This is highly subjective since the amount of confirmations one would wait for depends on the transaction size and health of the network. However, despite the subjectivity, we should make an attempt to calculate it. At the MIT Bitcoin conference, Nic Carter presented several ways we could quantify an adequate security budget:

Threshold: At a given level of security spend, Bitcoin is assumed secure

Stock: Security spend should be indexed to the value of Bitcoin itself

Flow: Fees must be large relative to transactional volume

I personally believe security is best measured as a percentage of stock whicheventually reaches a threshold level. Stock makes more sense than flow because miners will increasingly be focused on long term operations as ASIC efficiency diminishes. Eventually, this reaches a threshold level that will be extremely difficult to disrupt by even the most wealthy states.

I hypothesize several hundred billion, in present value USD, would be an adequate security budget since it would be very difficult for a government to justify such a waste of an expense to just 51% attack the tip of the Bitcoin blockchain. They would also have to respond publicly for such an attack as their citizens (taxpayers), businesses, and banks will all be invested in Bitcoin.

Note that a 51% attack wouldn’t “kill” Bitcoin, as you still cannot reverse historical transactions easily, the effort of which is calculated here.

“This may also increase the value of the fee market as demand to move Bitcoin should increase, creating more incentive for non-attackers to service the fee market” — Neil Woodfine

Finally, in the absolute worst case scenario of a sustained 51% attack, the thing that must be preserved is the UTXO set (ledger). If SHA256 must be abandoned, so be it. In that case, Bitcoin could fork onto a different mining algorithm that already has an established market — rendering all nation state mining equipment invalid. I want to be clear, this would be a last ditch effort, and by no means guaranteed to succeed, but the simple fact this could occur may dissuade a nation state from trying such an attack.

It’s important to note that PoW achieves other goals than just minimizing 51% attacks, and increasing network effect, it also ensures that money is provably costly to create (Unforgeable costliness).

I’ve paired a song with this article because I think it fits the feel of the piece and adds additional depth.

Bitcoin’s block space is a scarce and unique commodity

There is no alternative to prime real estate

Getting a transaction mined can be seen as purchasing a portion of a block. By analogy, on average every 10 minutes, a fixed amount of land is created, people wanting to make transactions bid for parcels of this land. The sale of this land is what supports the miners even in a zero-inflation environment. The price of this land is set by demand for transactions because the supply is fixed and known. The basic premise is that if the network is being used/valued then it will reward miners for validation/protecting the network.

Some argue that altcoin block space is an equal substitute. However, there are many ways we can debunk that theory. Bitcoin real estate is prime real estate (ex: it doesn’t matter how cheap land is in Midland, Texas, it’ll never have the views or social network of San Francisco and therefore will have less demand). The unique value of Bitcoin’s block space is due to security,exchange, volatility, and coordination costs.

This following section borrows heavily from Donald McIntyre’s article “Observations About Paul Sztorc’s Bitcoin “Security Budget in the Long Run” Essay” (I have his permission to use large directly quoted sections without quotations so the article could have more continuity)

Security costs: Bitcoin is the most secure cryptocurrency network due to the total accumulated hashes (energy). This will create a market for high value, highly secure transfers in Bitcoin, e.g. central banks, governments, interbank, corporate and other large value payment users, who will gladly pay very high fees. There is also a security feedback loop as other chains borrow Bitcoin’s strong security by making on chain transactions, as we’ve recently seen with Veriblock.

Exchange costs: When senders and receivers want to store value in Bitcoin, but need to transfer them, there is friction to move from BTC to an altcoin, send it for a lower fee, and then pass it back to Bitcoin on the other side. Between exchange commissions (0.1–4%), spreads (since alts are less liquid), and transaction fees both ways, there will be an indifference point beyond which it will be better to pay for Bitcoin fees. If Bitcoin is a very good store of value, transfers will occur within Bitcoin precisely for the same reason it is a good store of value.

Volatility costs: Often people forget to consider volatility costs which depends on your holding period. Altcoins typically have higher volatility than Bitcoin which has the nasty effect of scaling with transaction size. A hypothetical example:

LTC: $10 payment + 10% vol + 0.01 fee = $1.01

BTC: $10 payment + 1% vol + 0.20 fee = $0.30

LTC: $100 payment + 10% vol + 0.05 fee = $10.05

BTC: $100 payment + 1% vol + $1.00 fee = $2.00

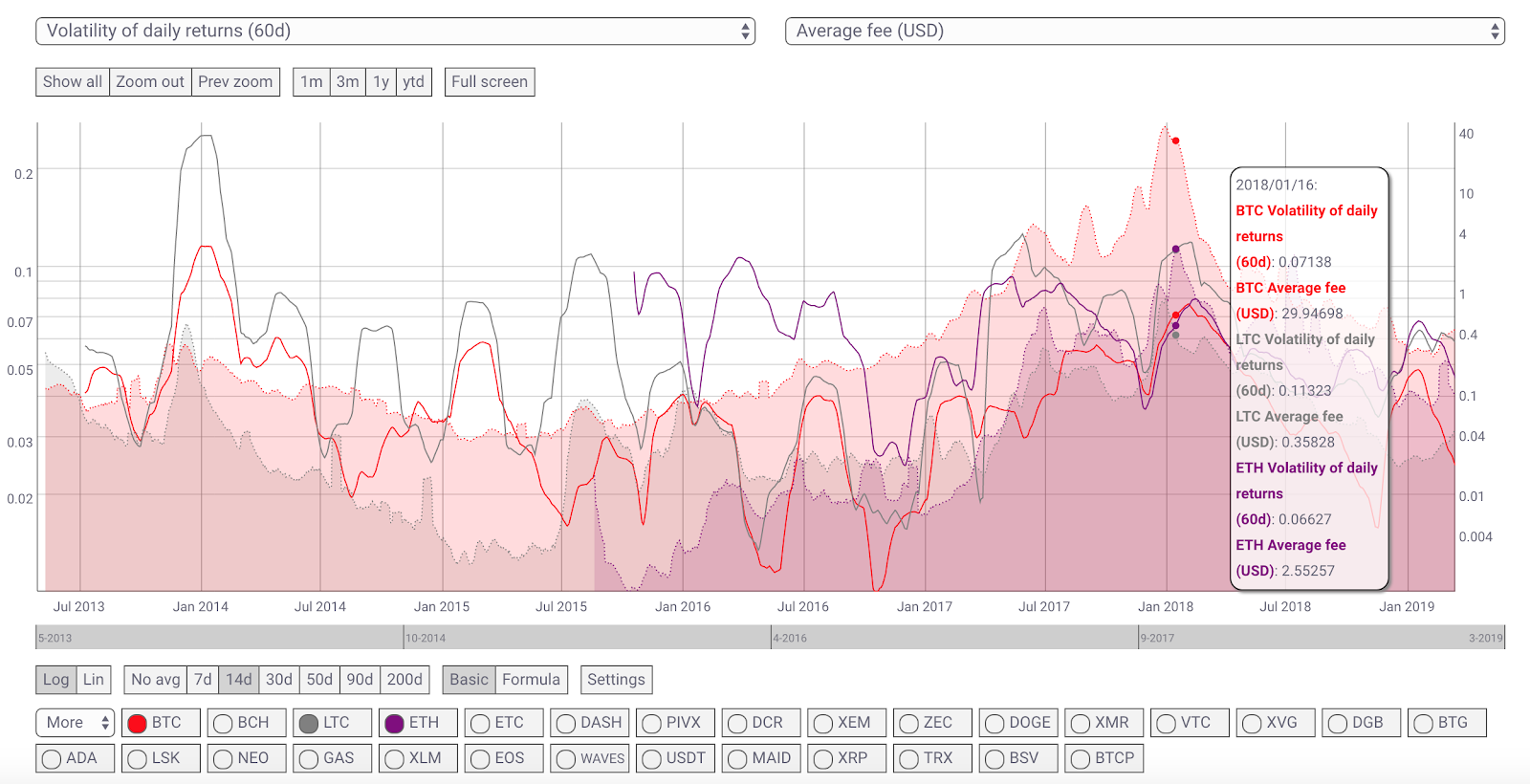

While Bitcoin fees hypothetically increased 5x, the volatility loss on LTC made the transaction fee ~$10! Conversely, even if you make money on the volatility, you still will have to pay capital gains. Below is a chart which shows average fee and volatility for BTC, LTC, and ETH. Unfortunately, without an average individual holding period for multiple coins, it would be difficult to calculate the average cost of volatility.

Coordination costs: Not all coins will survive. There will be a limited competing block space market in the world. This is because our minds are limited and we will not think about 250 cryptocurrency names, transfer fees, the subsequent 250 prices, and go about selecting the cheapest one each time we move value (@NickSzabo4). Our brains will only support understanding the value of 2 to 3 coins at most, and we will be comfortable using them interchangeably up to a certain point (although there is a weak/unproven case to be made for obfuscating a plethora of coins behind proper UX/UI). Additionally, since Bitcoin HODLers have a strong affinity to only transact in Bitcoin (monotheistic), multicoiners will be forced to transact in Bitcoin (Tyranny of the minority). For example: Square, Bakkt, and Fidelity are only supporting Bitcoin at this time.

Finally, the Bitcoin core software is battled hardened with a mature ecosystem. This adds value to Bitcoin’s unique block space since there are more developers and businesses that examine and rely on Bitcoin’s code.

“Bitcoin is money. Multicoinery is barter.” — Conner Brown

With all of these considerations above, there will be a limited amount of coins in the future, with a limited amount of block space and transaction capacity. This means that the cost of sending value will be distributed between the surviving chains in proportion to value and safety requirements. But in the end every altcoin is offering a lower security model with a higher risk.

“If one chain becomes the most secure by far, why would the majority of wealth and valuable apps not be secured by it? As more users buy into more secure chains, their buying pressure will push up the price. The increased price will lead to increased security. From there, eventually usage, liquidity, and network efforts will compound on each other. These most valuable and secure chains should then be used to secure the most wealth and valuable dapps. Less valuable blockchains with the same security model of their more expensive counterparts will become less and less used as the gap in security grows. Sidechains, layer 2 systems, etc. will make the ‘differentiating features’ of alternate chains less and less relevant.” — Alex Sunnarborg

“The sudden multiplication of altcoins and ICOs during the last bull run was a race to mimic the wealth creation that happened in Bitcoin. It was not millions of people suddenly using blockchains to transfer money around the world and seeking to minimize those fees. In other words, the coincidence of altcoin and ICO proliferation with the 2017 crypto bubble was a generalized gold rush (we were all trying to find gold/SoV) but not a rational pricing dynamic and arbitrage of block space through transaction fees.” — Donald McIntyre

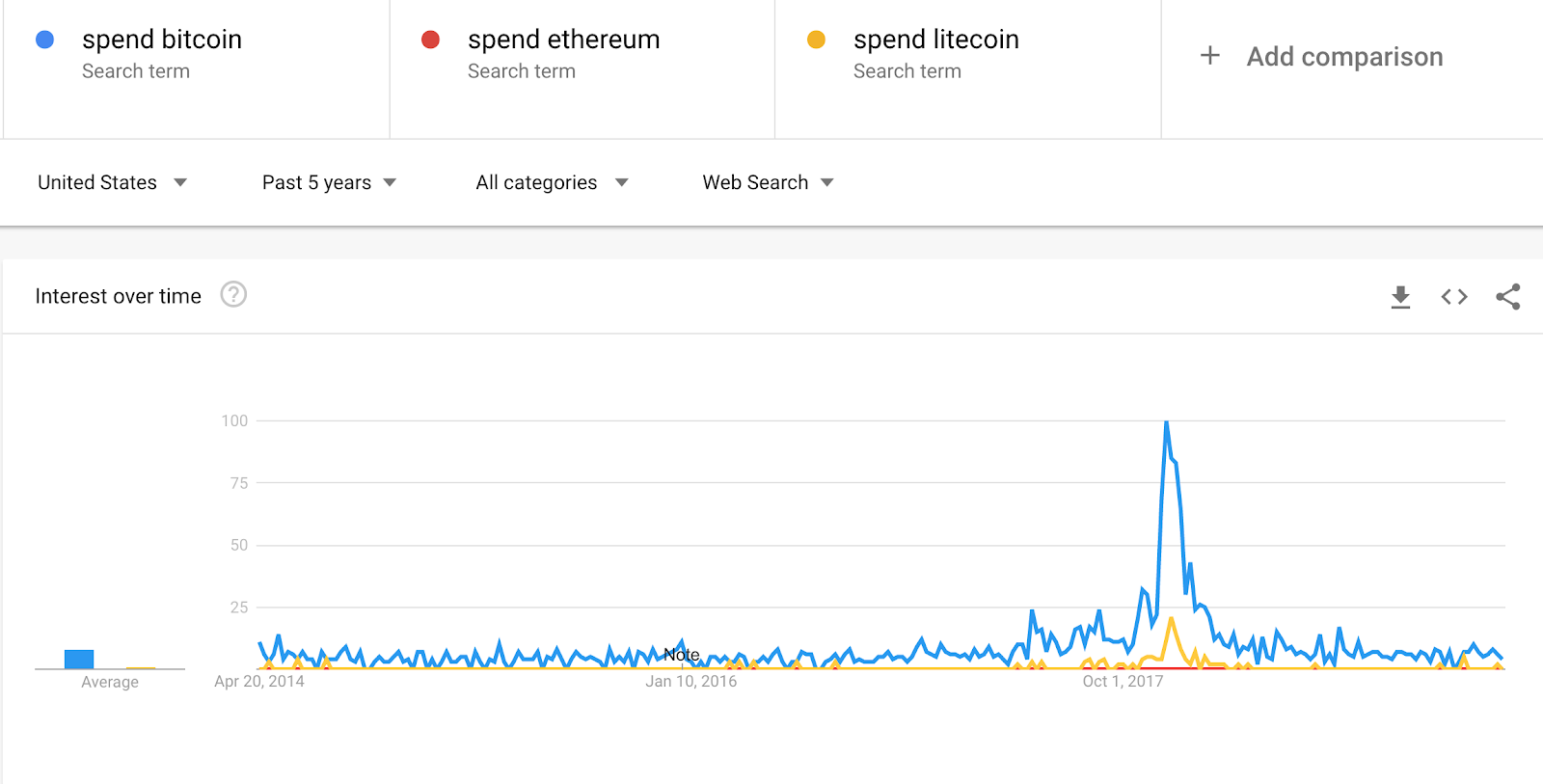

Although I have little data to back this statement up (and it’s quite subjective), I think a large portion of payments were likely done for novelty. Paying for something with crypto is harder, more expensive, and slower than traditional payment methods. After all, Bitcoin’s base layer is for building the strongest possible foundation for a new global monetary system–not creating another Venmo.

(If I had used the query “bitcoin” then “spend bitcoin” didn’t even register on the chart)

(Users aren’t looking to pay for items with any cryptocurrency, otherwise we would have seen an up trend despite the price volatility)

Transactional Demand

“I’m sure that in 20 years there will either be very large transaction volume or no volume.” — Satoshi Nakamoto

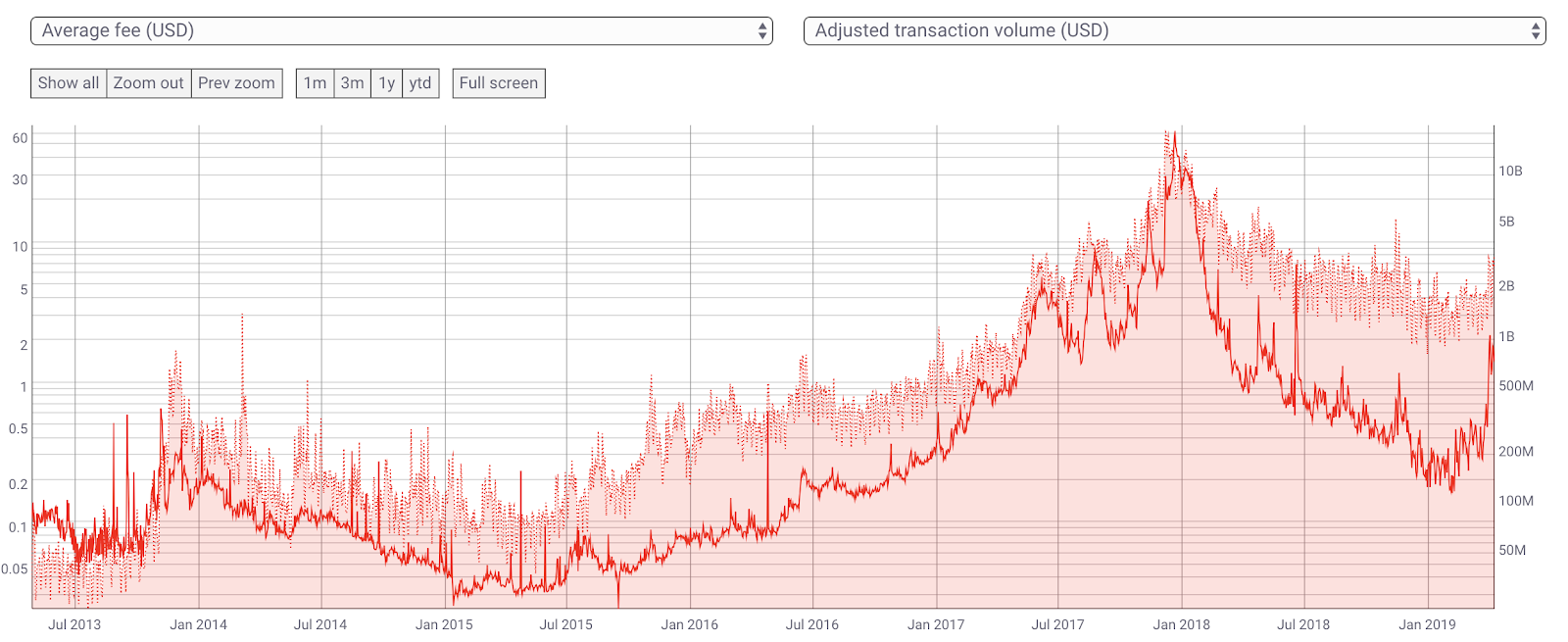

Another worry is that as fees become higher users will shy away from transactions to avoid fees. However, we’ve seen empirically this is not the case: as transaction/trading volume has increased, fees follow in step.

(log)

Price Elasticity

“Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.” — Yogi Berra

Consider the user experience for most North American, European, and Asian consumers/businesses (the majority of crypto participants). In most cases, any transaction fee has a higher level of friction than existing payment methods, so any fee is deemed “expensive” (vs cash or credit card).

“Think of the fees like insurance. You’re paying for security.” — Ari Paul

The price inelasticity (for fees) of a Bitcoin transactor is largely due to the nature of the payment type being sent, an immutable SoV. During the point of highest congestion in 2017, the median fee was $38. And during that time period, we briefly saw blocks with fees being greater than the subsidy. For comparables we can look at cost of transacting a SoV:

Wiring Fiat

For US banks, the average domestic wire fee is $30–40, and $65–80 for international (both incoming and outgoing fees combined).

Offshore ($7T Market)

“The setup fee for opening an offshore bank account is between…. $1,935 to $3,745 for [a bank account and an entity filing]” — Offshore Banking Primer

Real Estate ($250T Market)

“Buyers from China bought 40,400 units totaling $30.4 billion between April 2017 and March 2018. They spent a median of $439,100 per purchase” — National Association of Realtors

Average closing costs on a home are 2% of the value, or $8,000. I’m sure individuals will be fine paying $50 in the future to send an immutable payment with an asset that can’t be easily taken away from them (unlike real estate which could be seized in a geopolitical quarrel at the snap of a finger).

Physical Gold Delivery ($7.5T Market)

Donald McIntyre requested information from the Bundesbank regarding their NY Fed transfer of 300 metric tons of gold ($12 Billion at the time) from NYC to Frankfurt. It took 3 years and cost $4.8 million.

With smaller sizes, gold delivery may require insurance, verified shipping, or physical protection during pickup/delivery, etc. Estimated to be around $10-$100 at a minimum.

Increasing Transactional Density

Nic Carter’s MIT presentation highlighted two ways to improve transactional demand: increase economic or semantic density of transactions. Semantic Density is about having other blockchains imbed their data into the Bitcoin blockchain, like Veriblock. Economic density is about increasing transaction types on Layer 1, which are the following:

Privacy

“Schnorr can enable the creation of new transactions types that break the heuristics widely used in blockchain analysis, and make it nearly impossible to pinpoint specific entities by simply looking at the blockchain while simultaneously allowing greater transaction density per block by aggregating signatures.” — Lucas Nuzzi

Layer 2 (ex: Lightning)

As Bitcoin scales (Schnorr on Layer 1, Lightning on Layer 2, etc), it will become more and more efficient, driving higher on-chain usage. Jevon’s Paradox intuitively predicts this — as cars have become more fuel efficient, more miles are driven annually. Layer 2 will support a massive number of cheap smaller transactions, whereas Layer 1 represents a more expensive settlement layer for large transactions (container ships vs cargo containers — Nic Carter). LN boosts on-chain fees by increasing the utility of each on-chain txn (by allowing each to do the work of many txns), and by therefore making high on-chain fees more tolerable to the end user.

As businesses and Lapps are built around the Lightning network, a big part of their opex will be channel management. That will ensure constant demand for Layer 1 settlement as these operators rebalance channels and optimize connectivity & capacity. On-chain, block space is premium, hence transactions are charged for the space it takes to register the transfer. Off-chain, liquidity is premium, hence transactions are charged for the amount being transferred over the channels (as it requires rebalancing). In other words, on-chain and off-chain transactions have different fee models that complement each other. On-chain, the fee is constant despite transaction value, whereas off-chain the fee is priced as a percent of the value transfer. There is a crossover point where high value transactions cost more to use on Lightning than Layer 1.

We’ve already seen evidence that Lightning is increasing layer 1 usage, even in its highly experimental form. There was a block created in February 2019 which was 25% full with lightning transactions to open a channel. This was detectable because Lightning uses the SegWit malleability fix, all LN channel opens are SegWit transactions.*

“The nodes in the lightning network gossip information about which (public) channels exist in the network, including a reference to the funding tx, which we check to make sure the announcement is real. Which is an underestimate as there are also some number of private/unadvertised channels.” — Snyke

Quantum resistance

“The adoption of quantum resistant techniques will also result in larger (and more expensive) transactions. Post-quantum crypto algorithms require larger key sizes, which in turn increase the size of non-witness data in a transaction.”— Lucas Nuzzi

Overall

We have empirical evidence that total fee revenue will slowly trend up to equal the block subsidy in the coming decades. Based on this data, fears that the transaction fee won’t replace the block subsidy are definitively overblown.

The chart below shows transaction fees as a percentage of the block subsidy.

Chart and projections by Awe and Wonder. Y-axis is transaction fees as % of block subsidy.

As Alex Sunnarborg pointed out, only Bitcoin and Ethereum have meaningful enough transaction fees to compensate miners in a no inflation environment. It is very unlikely that any other network will be able to compete.

Data from CoinMetrics, Chart initially compiled by Alex Sunnarborg

Security Stability

“The volatility of fees, which seem to behave nonlinearly as blocks become full. Might lead to corresponding big swings in hashrate.” — Nick Szabo

Scarce block space is a good thing since we will see a backlog of transactions, which demonstrates future intent to reward miners, which in turn stabilizes the system. Congestion in 2017 demonstrated that the system can create and sustain a backlog.

A legitimate concern is that in a pure transaction fee security model, there will be volatility in cash flows. Transaction fees are market-centered, meaning that they go up and down adjusting to supply and demand. The base assumption is that cash flows from transaction fees will be unstable which makes the network less secure. Dan Mcardle sums it up nicely:

“As mining becomes highly commoditized with mature corporations, miners are unlikely to play short-run games, but will rather choose to mine continuously. Taking this further, as miners will likely vertically integrate with other services (ex: OTC) that become additional profit centers (meaning they’re not as concerned about the possible games to play on a block-by-block basis)” — Dan Mcardle

Miners like stable cash flows, hence why they join mining pools. They don’t play short term games trying to win a block, they socialize the winnings.

Given the worst case scenario where mining fees are unstable, it doesn’t actually undermine the system, it just makes settlement time longer until fees grow large enough for mining to turn back on. Entities, by necessity of time preference, would increase fees in response, countering.

Moreover, the subsidy has already been incredibly volatile in real terms over the past few years and mining has remained strong and constant–even with 80% drawdowns in the value of the subsidy. This “instability” has not affected the network and mining will continue to become even more resilient to large swings as the market continues to mature.

In the future, miners might auction space in future blocks in advance which could have a stabilizing effect on their revenue (the same way farmers sell crop futures). The basic premise is that if there is increasing usage of Bitcoin, the free market for future block space will price it correctly.

Finally, if this is a major issue that isn’t corrected by the market naturally, there are minor changes we can make in the protocol to smooth fee revenue. However, this would make the base protocol more complicated, and the game theory behind it hasn’t been adequately explored. For example:

“Other longer term low subsidy era ideas include fee averaging across block intervals to smooth fee revenue.” — Adam Back

Modeling Security Post Subsidy

What do transaction fees in a post block subsidy world look like? I built a model that would help us think through what they might be in the year 2140 (in today’s dollars), with a few necessary assumptions that you can view for yourself below. In its most congested state in the year 2140, a transaction on layer 1 may only cost between $8 — $82 depending on Bitcoin’s market capitalization. Transacting on layer 1 will be an infrequent occurrence for most consumers, just like wiring money.

$10T Market Cap

You can play around with the model here if you’d like to plug in your own assumptions.

$100T Market Cap

You can play around with the model here if you’d like to plug in your own assumptions.

Assumptions

Hyperbitcoinization

Bitcoin survives, thrives, and continues to grow in market share exponentially, as it has done the last 10 years. I’ve chosen Bitcoin’s max market cap in hyperbitcoinization value to be between $10T (value a bit higher than gold) and $100T, which has been a popular estimate for bulls. To put this value in perspective:

Total wealth in the world: $750T

Real Estate: $225T

Fiat: $50T-100T

Gold: $7.5T

Block size

Block size is constrained by latency, bandwidth, and storage. Without fundamentally changing how packet routing works, or advancing speed of transfers improvement in latency, picking a growth rate just based on bandwidth or storage increases isn’t the correct way to look at it (Another consideration with latency is usability with Tor). We have to look at the issues with larger blocks size holistically.

Certainly, a larger block size would alleviate some of the explicit fee pressure felt by transactors (thereby decreasing public scrutiny by ill-informed critics, and perceived “cost” for transactors). However, that offsets the cost onto node operators, simultaneously decreasing decentralization in some manner, which is what makes Bitcoin valuable in the first place. Also, this increases mining pool centralization. What level of centralization is allowable is a continuing debate in the Bitcoin community.

There is a case to be made for a market mechanism that would compensate node operators. For example: prompt relays, transaction data, SLAs, etc. However, it is mostly theoretical at the moment.

If a rate of block size increase is decided on, it should have a decreasing growth rate (similar to Bitcoin’s inflation rate). Otherwise, we are going to have to agree to softfork a smaller limit in later, which is the exact opposite of the position we want to be in. Some research has shown that 8MB might be the largest block size possible without material detrimental effects.

And finally, there have been some discussions around decreasing block time, which would provide the ability to further increase block size.

Layer 1 Efficiency

With Schnorr signatures (soon to be implemented), it is estimated that this upgrade would reduce the use of storage and bandwidth by at least 25%. We can assume some additional efficiency gains will occur over the next 120 years (Taprooft/Graftroof on the immediate horizon).

In the chart below, we can see that transaction fees as % of market cap trend towards a little above 0.001% daily over the next decade. Even with the continual decline of the block subsidy, total mining revenue (ie security) has increased exponentially as Bitcoin gains further adoption.

Chart and projections by Awe and Wonder. Left Y-axis is daily mining revenue in USD. Right Y-axis is transaction fees/block subsidy as % of market cap.

TPS

Assuming that current Layer 1 is 20 TPS max w/ Segwit. TPS depends on the byte size of the transaction but I had to choose a value to build the model.

Flawed Potential Solutions

Proposals for increasing the 21M hard cap, or “unlocking” dormant coins, aren’t appropriate to bring up at this stage for three reasons:

Lack of evidence that the decreasing block subsidy will be an issue

The divisiveness of the ask due to its ethical tradeoffs

More palatable fixes if there is an issue at least a decade from now

Conclusion

I’ve addressed what an adequate level of security could be, Bitcoin’s prime (and unreplicable) block space, transactional demand, what happens when the subsidy runs out, and security stability. We have empirical evidence that there will be proper security budget financing will equilibrate through fees. The tradeoff is always between inflation (block subsidy) and fees and Bitcoin is the best positioned to charge fees reliably. If there is no economic (transaction) volume in 10 years bitcoin will have failed anyway.

Most well-pedigreed critics predicting doom and gloom used absurd assumptions in their models.

Conversely, Cypherpunks write code.

Satoshi was essentially an academic that wrote production code, and published working models in the environment first focusing on practical implications.

His experiment, Bitcoin, has worked for 10 years despite an intensely hostile environment — all data indicates we have reason to believe it will continue to thrive.